History:

Geologists put the age of rock-salt found in Khewra at about 600 million years. In geological timescale this time period is calledPrecambrian.  It is said that discovery of rock salt in Khewra area dates back to as early as circa 326 BC. According to a legend, the army of Alexander the great was resting in Khewra area after a battle with Raja Porus. Some horses ofAlexander‘s army were then seen licking rock salt in the area. Somebody from Alexander‘s army noted down the incident in his ledger or diary and hence?we came to know that salt was discovered?here circa 326 BC.?History is however silent?on which language this incident was recorded in (Greek?) or where is that diary now. But since those days people in the area continued to collect salt from the out crops of salt seams that were exposed at the hill surface.

It is said that discovery of rock salt in Khewra area dates back to as early as circa 326 BC. According to a legend, the army of Alexander the great was resting in Khewra area after a battle with Raja Porus. Some horses ofAlexander‘s army were then seen licking rock salt in the area. Somebody from Alexander‘s army noted down the incident in his ledger or diary and hence?we came to know that salt was discovered?here circa 326 BC.?History is however silent?on which language this incident was recorded in (Greek?) or where is that diary now. But since those days people in the area continued to collect salt from the out crops of salt seams that were exposed at the hill surface.

It is said that discovery of rock salt in Khewra area dates back to as early as circa 326 BC. According to a legend, the army of Alexander the great was resting in Khewra area after a battle with Raja Porus. Some horses ofAlexander‘s army were then seen licking rock salt in the area. Somebody from Alexander‘s army noted down the incident in his ledger or diary and hence?we came to know that salt was discovered?here circa 326 BC.?History is however silent?on which language this incident was recorded in (Greek?) or where is that diary now. But since those days people in the area continued to collect salt from the out crops of salt seams that were exposed at the hill surface.

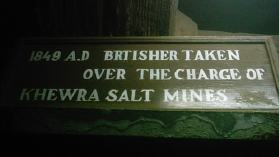

It is said that discovery of rock salt in Khewra area dates back to as early as circa 326 BC. According to a legend, the army of Alexander the great was resting in Khewra area after a battle with Raja Porus. Some horses ofAlexander‘s army were then seen licking rock salt in the area. Somebody from Alexander‘s army noted down the incident in his ledger or diary and hence?we came to know that salt was discovered?here circa 326 BC.?History is however silent?on which language this incident was recorded in (Greek?) or where is that diary now. But since those days people in the area continued to collect salt from the out crops of salt seams that were exposed at the hill surface. It is said that the chiefs of‘Janjua-Raja’ tribe were the first to initiate the standard mining practices here in the13th Century. However, a chronology of the Mughal Rule in the Sub-Continent says that when the Mughals emerged supreme in the Punjab, they took over the mine from the local tribal chiefs and, thereafter, started to work on it until Punjab came under the Sikhs. Under Sikh rule the mine came up to be known as ‘Khewra Salt Mine’. The British ousted the Sikhs and annexed Punjab in 1849 and renamed the mine as the‘May Mine’ in 1870.

It is said that the chiefs of‘Janjua-Raja’ tribe were the first to initiate the standard mining practices here in the13th Century. However, a chronology of the Mughal Rule in the Sub-Continent says that when the Mughals emerged supreme in the Punjab, they took over the mine from the local tribal chiefs and, thereafter, started to work on it until Punjab came under the Sikhs. Under Sikh rule the mine came up to be known as ‘Khewra Salt Mine’. The British ousted the Sikhs and annexed Punjab in 1849 and renamed the mine as the‘May Mine’ in 1870.In 1872, Dr. H. Warth, a renowned British Mining Engineer, laid out the main tunnel at ground level.  He proposed that only 50% of salt be excavated from the working seam while the remaining 50% be left as pillars. 155 years later this same methodlogy called the ‘room and pillar’ method is still being used in Khewra mining operation.

He proposed that only 50% of salt be excavated from the working seam while the remaining 50% be left as pillars. 155 years later this same methodlogy called the ‘room and pillar’ method is still being used in Khewra mining operation.

He proposed that only 50% of salt be excavated from the working seam while the remaining 50% be left as pillars. 155 years later this same methodlogy called the ‘room and pillar’ method is still being used in Khewra mining operation.

He proposed that only 50% of salt be excavated from the working seam while the remaining 50% be left as pillars. 155 years later this same methodlogy called the ‘room and pillar’ method is still being used in Khewra mining operation...Photo to the left shows rail tracks in the main tunnel of the mine. Can you also see some ghosts walking in the tunnel….

To make salt from Khewra mines accessible to rest of India, British laid a railway line which was opened as a meter-gauge on January 1, 1883. It was later converted to a siding and a broad gauge line was laid which is operational to date.

Salient Features:

Khewra salt mines are the second largest salt mines in the world, outdone only by Wielicza salt mine in Krakow, Poland.

At present the Khewra Salt Mine is in the control of a federally controlled corporation i.e. Pakistan Mineral Development Corporation (PMDC).

.. Photo to the right is the main entrance. The date written on top-middle of this arched gate is 1916-17. The Urdu sign reads ‘Salt Mine Khewra’ which is literal translation of English text to the left. Until few years ago the sign in Urdu had Persian influence and it used to say ‘kaan-e-namak Khewra’. Sign of changing times!!…

.. Photo to the right is the main entrance. The date written on top-middle of this arched gate is 1916-17. The Urdu sign reads ‘Salt Mine Khewra’ which is literal translation of English text to the left. Until few years ago the sign in Urdu had Persian influence and it used to say ‘kaan-e-namak Khewra’. Sign of changing times!!…Ok. Get ready to digest some numbers in this paragraph. There are19 levels (similar to stories in a building) in the mine. Seven levels are above ground and twelve are underground. There is a clearence of 50ft of salt/rock between each level. Annual extraction of salt here is around 315000 tonnes (in 2003-04). The mine is 350m above sea level and goes 730m deep into the mountain. The cumulative length of tunneling which is done inside the mine is more than 40 km. Inside the mine there are seven rock salt seams with an accumulated thickness of 150 metres.

In spots the rock salt is 99% pure. Some people say salt or no salt, it is hard to find anything so pure outside the mine these days. The average purity however is around 96%. According to PMDC website the salt deposits here are 6.687 billion tonnes. It was difficult for me to imagine how much salt is that but at another website I read this is enough deposit for 400 years (unconfirmed). It must also depend on how much salt is extracted every year.

What to See:

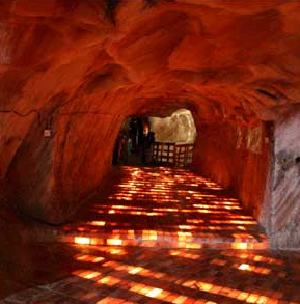

Since 2002, the main tunnel of the mine has been converted into a tourist attraction. Some of the websites we consulted claim 35000-40000 visitors come here every year. In 2003 a major restoration work was carried out at the mines to make it a prime tourist destination.  Decorative light-work was done to make portions of mine a walk through the glittering stars. The salt crystal found here is translucent?which means it absorbs some light and reflects some.

Decorative light-work was done to make portions of mine a walk through the glittering stars. The salt crystal found here is translucent?which means it absorbs some light and reflects some.

Decorative light-work was done to make portions of mine a walk through the glittering stars. The salt crystal found here is translucent?which means it absorbs some light and reflects some.

Decorative light-work was done to make portions of mine a walk through the glittering stars. The salt crystal found here is translucent?which means it absorbs some light and reflects some...Photo to the right shows a wall made of salt bricks. Notice the different shades of rock salt under light..

Depending upon the thickness (among other properties), the salt rock glows when lit in many different shades.

The tourist attractions inside the mine include:

(1) Assembly Hall: It is the name given to?a large chamber in the mine. It measures about 75m in height and fascinates tourists because stairs go circling around the hall to the top.

(2) pul-saraat: This is a Salt Bridge called the Pul-saraat. It?has no pillars whatsoever to support it. It is just a narrow strip of pure rock salt 20 to 25 feet in length and 5 feet thick with 80 feet deep ponds of brine (Saltish Water) on both sides. Those who know the meanings of real pul-saraat must be enjoying the creativity of people who thought about naming this salt bridge as such.

(3) Indoor Brine Ponds:

Inside the mine there are certain chambers filled with saturated brine solution. The salty water seeps through mine walls and roof and collects into these chambers overtime. There are several such water-filled chambers in the mine but they are very difficult to see in the dark. Only two such ponds have been illuminated for tourism purposes. One such pond is shown in the photo to the left.

Inside the mine there are certain chambers filled with saturated brine solution. The salty water seeps through mine walls and roof and collects into these chambers overtime. There are several such water-filled chambers in the mine but they are very difficult to see in the dark. Only two such ponds have been illuminated for tourism purposes. One such pond is shown in the photo to the left.(4) Badshahi Mosque: There is a mosque built inside the main tunnel of the mine.  It is called the ‘badshahi masjid’. To beautify the mosque different colours of salt bricks have been used. Red, Pink and White are the major shades of salt bricks. Between the Bricks space has been provided for the electric bulbs to lit the mosque.

It is called the ‘badshahi masjid’. To beautify the mosque different colours of salt bricks have been used. Red, Pink and White are the major shades of salt bricks. Between the Bricks space has been provided for the electric bulbs to lit the mosque.

It is called the ‘badshahi masjid’. To beautify the mosque different colours of salt bricks have been used. Red, Pink and White are the major shades of salt bricks. Between the Bricks space has been provided for the electric bulbs to lit the mosque.

It is called the ‘badshahi masjid’. To beautify the mosque different colours of salt bricks have been used. Red, Pink and White are the major shades of salt bricks. Between the Bricks space has been provided for the electric bulbs to lit the mosque...Photo to the right shows Badshahi mosque inside the main tunnel of Khewra Salt Mine..

(5) Sheesh Mahal:?The word Sheesh Mahal means ‘Palace of Mirrors’. There is an area called Sheesh Mahal in the mine named such for?colorfully reflecting salt bricks. The salt here is of light pink color and glows in many different shades under light.

(6) The Great Wall of China, The Mall, Shimla Hill andMeenar-i-Pakistan:

The salt walls of the main tunnel has carvings of some famous structures which glow under light in beautiful shades. These wall carvings include models of the Great Wall of China, the Mall road of Murree, Lahore’s Shimla hill, Minar-e-Pakistan Lahore etc. All these structures are made of Salt that emit pink, white and red lights when lit up.

The salt walls of the main tunnel has carvings of some famous structures which glow under light in beautiful shades. These wall carvings include models of the Great Wall of China, the Mall road of Murree, Lahore’s Shimla hill, Minar-e-Pakistan Lahore etc. All these structures are made of Salt that emit pink, white and red lights when lit up... Photo to the?left above?is a carving of meenar-e-Pakistan made by salt bricks. The dimensional?scaling of this model as compared to the real meenar-e-Pakistan is extremely violated here but we should not keep it against the artists?of Khewra mines…

(7) Narrow Gauge Electric Railway:

A narrow gauge electric train transports visitors from the visitors gate to a track juncture some 500m inside the tunnel. Outside the tunnel one can also see abandoned rails and small train wagons that were used here for salt extraction since1930s.

A narrow gauge electric train transports visitors from the visitors gate to a track juncture some 500m inside the tunnel. Outside the tunnel one can also see abandoned rails and small train wagons that were used here for salt extraction since1930s...Photo of this train is given to the right.

The fare structure for this train is expensive and kind of complicated. Fare for a ride is Rs. 250. Twelve people of a group can ride in this fare. For any person more than a group of 12, the fare is Rs 20 each…e.g. 13 people in a?group will pay Rs 270 and so on..

(8) Pakistan Post Office, Khewra Salt Mine. Postal Code 48530

There is a fully functional Post Office made of salt bricks inside the Mine. One can send postal mail all over the World from here.

There is a fully functional Post Office made of salt bricks inside the Mine. One can send postal mail all over the World from here...A photo of this post office inside the mine built from Salt bricks is shown to the right..

There is a full time postal employee stationed here.

(9) Salt Crystal Formations

Such formations are abundant in the mine and are a big tourist attraction. Some of them seem to grow upwards from the ground while others hang from the roof. One such formation takes many decades to form therefore it is of utmost importance that tourists don’t touch or break them

Such formations are abundant in the mine and are a big tourist attraction. Some of them seem to grow upwards from the ground while others hang from the roof. One such formation takes many decades to form therefore it is of utmost importance that tourists don’t touch or break them..photo to the left shows crystal formation on the mine roof.

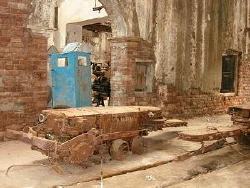

(10) Old Mining Machinery

Though not very well kept, one can spot old mining machinery as well as bits and pieces of old railway lying around here and there.

Though not very well kept, one can spot old mining machinery as well as bits and pieces of old railway lying around here and there... photo to the?right is of abandoned old rolling-stock which was in works circa 1930s..

There is also a briefing room for visitors as well as a sovenier shop located here. The mine is open 9 am to 6 pm all year round.

Chronology of Khewra Salt Mines:

326BC: Khewra salt deposits are discovered by the troops of Alexander’s army whose horses were seen licking rock-salt in the area.

13th Century AD: Janjua-Raja tribe extracts salt from the area.

1500: Mughals control the salt removal from the area

1809: Sikhs take over the control of mines from the Mughals

1849: British take over the control of mines from the Sikhs.

1850: British reports reveal that about 534512 tonnes of fine rock Salt had been extracted up to then.

1853: Drinkable water spring is discovered in the mine. Waterworks are built in the form of wooden pipe to transpost this water to Khewra village of that time.

1856: The metalled road between Khewra and Pind Dadan Khan is destroyed because of floods.

1870: British renamed the mines as ‘May Mines’.

1872: Dr H. Warth, the chief mining engineer at Khewra?designs the main tunnel at ground level and establishes 50-50 room and pillar rule of salt extraction.

1878: Dr H. Warth leaves the Khewra Mine Project.

January 1, 1883: Meter-gauge railway was opened from Chalisa to Khewra.

1886-87: Queen Victoria Railway Bridge over River Jhelum is completed. This connects Khewra to Malakwal Jn and hence to?all of India by rail.

1889-90:Salt production crosses 50000 metric tonnes for?the first time.

1902: A hospital is established to provide medical facilities to miners and their families.

March 1923: the production obtained from Khewra Salt Mines was 4971420 tonnes

1938: ICI Soda Ash Khewra Plant established.

1947: Government of Pakistan takes over the mine operation.

1974: Pakistan Mineral Development Corporation (PMDC) established.

2002: Khewra Salt Mines Resort Development Project launched by the PMDC Management.

How to get there:

Motorway M2:The fastest way to reach Khewra mines is via motorway M2. The mines are located 30km east of Lilla interchange towards Pind Dadan Khan. Road signs are quite visible.

Highway N5: A slower but scenic approach is also available from GT road?from Mandra.?Distances?from Mandra (0km)are:?Chakwal (63km), Choa Saidan Shah (93km) and Khewra (103km).

Pakistan Railway:

I will not recommend train link to Khewra unless you are a die-hard train fan. There are two trains daily between Malakwal Jn and Khewra which cover 27km distance in exact 1 hour. You have to change trains at Malakwal Jn which is connected to Lala Musa Jn on mainline at one end and Sargodha Jn at other. There are 6 daily trains on this Lala Musa – Malakwal – Sargodha route.

I will not recommend train link to Khewra unless you are a die-hard train fan. There are two trains daily between Malakwal Jn and Khewra which cover 27km distance in exact 1 hour. You have to change trains at Malakwal Jn which is connected to Lala Musa Jn on mainline at one end and Sargodha Jn at other. There are 6 daily trains on this Lala Musa – Malakwal – Sargodha route...photo to the left above is Khewra Railway station building..